Like Dust I Rise

Pushed over the edge by the hit and run death of a little boy in their Back of the Yards neighborhood, Nona Williams’ father, who works in a slaughterhouse, is determined to move his family out of Chicago. He brings home posters encouraging the homesteading of the Great Plains. At the same time, recent pictures of Amelia Earhart, the first woman to fly across the Atlantic, have sparked a dream of becoming a pilot in the mind of ten-year-old Nona. She mistakes plains for planes, and is excited to move where she thinks she might one day learn to fly. Like Dust I Rise, follows the Williams’ family to Dalhart, Texas, where they find temporary success wheat farming until the rains stop. Surviving the worst natural disaster in this nation’s history, becomes a daily struggle with tragic results as both Nona and her father cling tenaciously to their individual dreams, one of home ownership and the other to fly.

*

Research is more fun than writing. For Hurt Go Happy, I played with chimpanzees and orangutans. Dolphin Sky and How to Speak Dolphin, the obvious. Ditto with The Outside of a Horse. Lost in the River of Grass, included many hikes into the Everglades, but it was my 2014 trip to Texas to research Like Dust I Rise that was uniquely amusing.

I love to ride and write on trains. Since this novel begins in the old Chicago stockyards, I booked a train from Davis, CA, to Chicago to get a feel for the area, then continued on to Lamar, CO—as close as I could get to Dalhart, TX, the epicenter of the Dust Bowl and my novel.

To stay in a hotel near Union Station in Chicago was out of my financial league, so I reserved a single room in a hostel not far from Lincoln Park. Even as I disembarked from the cab, I felt every year of my advanced age. A rather intimidating set of concrete stairs lead to the entrance. Young people were coming and going. As I stood there, preparing to drag my wheelie up step by step, a young Frenchman said, ‘Let me get that for you,’ and ran up the steps with my bag, then held the door for me until I caught up.

My room had bunk beds, a small window out onto a garden, and a large black and white rendering of Che Guevara on one wall. Since I’d booked a single, I took the bottom bunk.

The hostel was in a residential neighborhood. Rather than search for a restaurant, I opted to eat in the dining room. I was so clearly out of my element that the hordes of young people took it upon themselves to help me navigate the protocols of hostel dining. This short little old lady stood in line for spaghetti, found, and hopped up on a tall barstool-like chair to dine at high-top table in the company of an amiable young man from Poland. It was from him that I discovered my arrival coincided with the next day’s Chicago marathon, which was expected to host 45,000 runners and 100,000 spectators. Best laid plans. I did my dishes and went to bed.

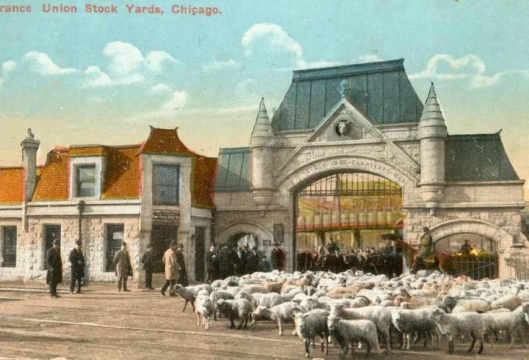

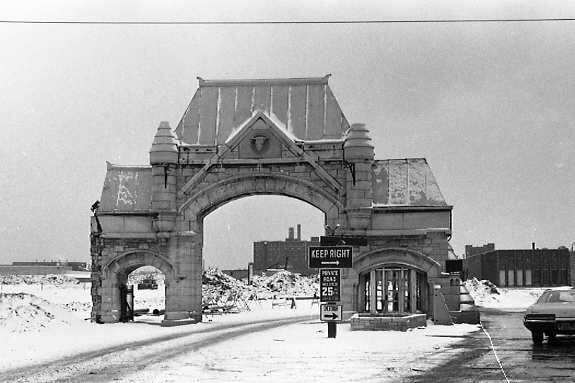

I awoke the next morning to shouts, cheering, and applause. Since my train to Lamar didn’t leave until the late afternoon, I got dressed and walked down to watch the runners. I never did get near the Back of the Yards neighborhood, or all that remains of the Chicago stockyards—the gate.

All that’s left of the stockyards.

The taxi ride back to Union Station was convoluted, consisting of back streets to avoid all the closures. The train ride was uneventful, though I continued to stress about whether I would really have a rental car when I got to Lamar, the nearest town on the Southwest Chief route to Dalhart, TX, a 150-mile drive south of Lamar. Earlier research for rental car agencies drew a blank, until a Hertz agent suggested I try Lamar’s Ace Hardware store.

In spite of not being aware that my Chicago visit coincided with a marathon, I rarely leave much to chance when I travel. A full year before I embarked on this trip, I took that agent’s advice and reserved a rental car from the Ace Hardware store. Every couple of months, I called them to make sure they still had a reservation for me. Many times, the person answering had no clue what I was talking about, which is why I was still nervous that a hardware store was the go-to place for a rental car, and why I continued to check until one of the clerks finally told me to stop worrying, they had three cars for rent and rarely rented any of them.

I arrived in Lamar early on a brisk, freezing cold October morning. The prairie winds, which I’d written so much about in the first drafts of this novel, were showing me their stuff. I wheeled my suitcase four or five blocks to the hardware store, bent into a wind strong enough to twice rip the handle out of my stiff, icy fingers, and topple my bag. Arriving at the hardware store, my concerns bubbled up again since the few cars in the parking lot looked harshly driven and not the least bit rentable. A knot formed in my stomach. If this didn’t work, I had no way to get to Dalhart, short of thumbing, and the entire trip would be wasted.

My goal in Dalhart was to soak in the atmosphere of the place considered the epicenter of the 1930s dust bowl, find an old school house, a working windmill, a dugout, the train station, and locate where exactly my fictional family lived. I’d made contact with the director of the XIT museum and planned to start there.

Inside the hardware store was modern, toasty warm, well-stocked, and crowded with men in overalls and John Deere caps. My elderly, invisible self remained unnoticed among the hubbub. When I did get someone’s attention and said I was there to pick up a rental car, the kid said, “Huh?”

My heart pounded.”I was told you rent cars.”

He picked up the mic and paged Bob or Joe, I don’t remember. “Yes, ma’am,” Bob or Joe said. “Got your car all ready for you.”

I found myself humming The Yellow Rose of Texas as I filled out the short, mimeographed form and showed my license. Joe/Bob walked me outside and across the lot to the cars I’d thought looked so worn out they belonged to customers or employees. Clearly, they got a deal, because there were three old maroon sedans in a row. Mine had a flat tire.

“We’ll have that fixed in pronto,” Joe/Bob said.

True to his word, as I waited under the overhang, wind whipping leaves around my ankles, he was back minutes later. “You’ll be needing some gas.” He handed me the keys.

I never did determine the make of the car, but it was ancient enough to lack a center console and the passenger side had a long stab wound that exposed the stuffing. The odometer reflected 158,000 miles of experience under its hood. And he was right, it needed gas. The needle was on empty. I filled up on the outskirts of Lamar and headed south.

Ninety-six miles south of Lamar, on US 385, I pass through Boise City, OK, as familiar to me as Dalhart was after reading and re-reading The Worse Hard Time by Timothy Egan. I’m now 49 miles from my destination, but I’m already feeling a sense of déjà vu, though I’d never been here before.

The iron sculpture was made possible by Bob and Norma Gene Young in 1990. It was a dream of Bob and Norma Gene Young to build a true scale dinosaur like the one that was excavated in Cimarron County by Dr. Stovall. This dream came true with the sales of Norma Gene’s book “Footsteps.”

Joe Barrington from Throckmorton, Texas built the 65 foot long, 35 foot high and 18,000-pound Apatosaurus. The dinosaur was named “Cimmy” by a Boise City Elementary student. This exact scale model of the Apatosaurus sits adjacent to the Cimarron Heritage Center.

***

I admit to a guffaw when I spotted this life-size dinosaur looming over the flat as a pancake landscape. The sign outside the little house read Cimarron Heritage Center, but since I was on a mission into the heart of this country’s greatest natural disaster of all time, and didn’t need to pee, I didn’t stop.

I’m not sure what I expected of Dalhart. Sand dunes, maybe. I admit to being disappointed, and this will not endear me to the residents of Dalhart, but the face it presents to the world is unattractive at best. It sits at the crossroads of two major highways and two railroad lines. My motel was backed up to one of the railroads and fronted on one of the highways. Semis rolled through night and day, as did trains. I found only two restaurants open—ever, one for BBQ and the other a diner for breakfast. It took me two days to find a grocery store where I stocked up on frozen dinners to cook in the microwave in my motel room.

On arrival, I went straight to the XIT Museum. Naturally, I’d made contact with the director earlier and was expected. The focus of the museum was to celebrate and preserve artifacts from the largest cattle ranch that ever existed—the XIT. There is speculation that it got its name because it covered 10 counties in Texas, thus the Roman numeral X stood for 10 in Texas. It’s a terrific little museum, but had little or no historical information on the Dust Bowl. (My visit was in 2014. They plan to open a Dust Bowl exhibit this year, 2021.)

I had another disappointment in store. Once again, I was looking for an old one-room schoolhouse, a working windmill, a dugout, and the train station. Sadly, according to the director, the train station was gone, there wasn’t an old schoolhouse left standing, he’d never seen a dugout, and didn’t know of a single working windmill. All, however, was not lost. They did have journals and diaries of people who lived through that era. During my four days there, I read dozens of these treasures, and drove around the county until I found a place southeast of town where my characters would in live.

Four days later, I departed Dalhart for the drive back to Lamar. I stopped in Boise City at the Bluebonnet Café for breakfast. I parked in front of the restaurant and an old man held the door for me. “That there’s a beaut,” he said of my car. I thanked him. My Nebraska born and raised father used to use the word ‘beaut’ mostly for the fish I caught in our lake in Florida. (Recently, one of the networks interviewed people in that very café. The question was, were any of them planning to get vaccinated? Unsurprisingly, the unanimous answer was no. During the newscast, I scanned the customers’ faces for that friendly old man.)

What the hell, I thought when I passed the Brontosaurus. The Open sign was out and I didn’t have anything to do until my train left the next morning. The house was a 1950s model, a style I recognized from my own upbringing. Inside the front door, was a little gift shop where I found a number of books written by locals about the dust bowl years. Judy Wilson, the woman behind the counter, asked where I was from, then told me she had a sister living 33 miles from my home in CA. What in the world brought be to all the way to Oklahoma? Mostly, I recall her enigmatic smile when I told her how disappointed I was not to have found any of the things I’d come all this way in search of. “Maybe I can help.” Judy crooked a finger for me to follow.

We passed through a 1950s living room, a 1950s kitchen, down a hall that once led to bedrooms, I suppose. It was lined with historical photographs. She unlocked a rear door and we stepped into a warehouse-sized building that I hadn’t noticed from the highway. It was divided into kitchen tableaus starting with 1890 and jumping in ten-year increments. Mannequins were dressed in period costumes and each kitchen was decorated appropriately for the decade. I was especially interested in the 1930 tableau.

“If you’re not in a hurry—” the enigmatic smile again. “I could show you around outside.” She opened the door to the backyard and stood aside.

I burst out laughing. The most obvious yard ornament was a working windmill. To my right was a complete train station with an old baggage cart on the platform. There was the station master’s office and coal storage. Next to it, a barn full of old prairie schooners, buckboards, and a Conestoga, which is what Nona’s father moved to Texas in. Beyond that was a fully furnished one-room schoolhouse.

I was just thinking the only thing missing. . . when Judy pointed me toward a mound of dirt in the middle of the yard. A dugout! It contained a bed, a washstand, and a wood stove. That was the moment my camera battery died, but I’d learned a lesson. Never look a gift dinosaur in the mouth.

Back in Lamar, and now a believer in small town museums, I located the Big Timbers Museum where I found a number of period pictures, which the curator was kind enough to email to me. She also told be about Granada, a Japanese internment camp located a short distance east of Lamar. The American citizens interned there successfully farmed it and their efforts were memorialized with display panels.

It was a warm day and I wandered the trail wearing my go-to footwear—flip flops, which resulted in my final and most lasting memory of my trip. I nearly stepped on a spider virtually the same color as the gravel path. It was about the size of my thumbnail but had an unforgiving chip on one or more of its shoulders. I stepped off the path to walk around it, but it charged me. I took a step back, and it charged again. I laughed and leaned down to look it eye to eye. It scuttled toward my bare toes. I jumped aside. Which ever way I moved, it followed until I was dancing from side to side, laughing at my own antics, and grateful to go unobserved. To honor the moxie of that spider, I added a scene with a tarantula to my story.